Personal experiences – spoken language and deaf pupils

A feature of this website is the inclusion of personal experiences of the topic under consideration. This makes it possible to include different perspectives, including accounts from professionals and consumers, and different views on decisions that have been made.

We welcome these contributions at any time, and guidance for contributors is given in the overview of the project section.

We are also happy to include here links to signed contributions.

Index

A personal history of the Maternal Reflective Method – Catherine Healey. Catherine had many years’ experience of teaching deaf children. She is now semi-retired.

Deaf Education – What was it like? – Trish Cope. Trish taught deaf children in several different settings and now works for the Ewing Foundation.

Teaching speech in the 1970s – Linda Watson. Linda’s early career was spent teaching in a school for the deaf and here she describes the daily speech lessons that children received.

Mandy – Sue Gregory. Sue watched and reviewed the film Mandy, which was produced in 1952. It is a fictional account of a deaf child learning to talk and play. There is a link to the film under ‘resources’.

John Tracy Clinic – Sue Gregory. Sue describes the correspondence course that the John Tracy Clinic offered to parents of young deaf children.

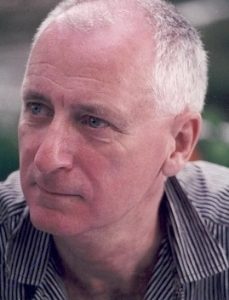

50 years on: The changing context of deaf education. David Braybrook. David Braybrook MA, FRSA reflects on changes in deaf education since the 1960s. He considers the impact of this on the teaching of spoken language. David is a Consultant Specialist in Special Educational Needs and has worked in this area for 25 years.

Catherine had many years’ experience of teaching deaf children. She is now semi-retired. The labels “Conversation Method” and “Maternal Reflective Method” (MRM) are often used interchangeably, as the importance of interactive communication is central. The term MRM is actually more helpfully descriptive, although these days using a gender defining term such as “maternal”, may raise eyebrows, particularly as many parents share the care-giving role. However, we still commonly refer to first language as “mother tongue”, and it is in this context that the term is used. It is important to start by explaining the words – maternal/reflective/method. But the MRM is far more – it is a communication approach, a philosophy, a whole way of thinking. RESEARCH: In 1968 a Dutch cognitive psychologist working with profoundly deaf children, Dr. A van Uden, first published “A world of Language for Deaf Children”, in which the words “maternal method” (p.179) and “reflective method” (p.37) were first used. Since these early days, many professionals working with deaf children have adopted and adapted this approach, which recognises the fundamental importance of sharing experiences or ideas with a child, giving the child our full attention, listening to what the child has to say, helping him/her to say it, responding and developing a shared conversational context, and providing the opportunity to re-hearse/re-live/re-create the experience or idea and reflect on it, with photos, words, videos, and more conversations. The MRM way of working does not necessarily restrict itself to an oral approach, although it was originally developed as such. Several schools for the deaf in the UK have adapted the principle of using conversation as the basis for a reading text, in non-oral environments, which gives weight to its value as a worthwhile pedagogical approach. PRACTICE: I first heard of the MRM in 1980 and now in 2016, I am still using aspects of the approach in my work with trainee Teachers of the Deaf in Sierra Leone. For these teachers it is still a valuable pedagogy which puts the child at the heart of the learning process, and encourages the teacher to reflect, plan, reflect more, but most of all to LISTEN to what the child wants to say. PERSONAL HISTORY: Five short anecdotes! In 1981 as a newly qualified teacher, I found myself unexpectedly working temporarily in a special school for deaf children. After a term of muddle and confusion I was in distress and ready to give up, but a colleague returning from the MRM course in the Netherlands took me in hand and explained the basic principles of what was then called the Conversational Method. This included the crucial tip – if in doubt, write it down. Hurrah! At last I had a procedure to follow – talk and listen, create a text for reading practice, talk, listen and read some more. The text was not just for reading; it was a way of keeping our shared ideas together in words, exploring not only language but my whole relationship with the children, their relationships with one another, and most importantly, it gave them the lead. I learnt that the MRM engenders joint attention and mutual respect. In 1985 van Uden requested that a group of children come to the Netherlands to demonstrate his MRM approach in English. So, I and my year 6 class, travelled on the overnight ferry to have our “conversation” and “reading lesson” in front of some 100 teachers from all over the world. It was a bit nerve-racking for all of us, but very exciting. We certainly didn’t lack for shared experiences and ideas. I hadn’t met van Uden before and was glad to learn more about the “method” from him as he observed me teach. One incident sticks in my mind. He jumped up from his seat and cried: “NO, we must never avoid the figurative, the figurative! The figurative is the spiritual life of the child.” – when I was afraid to explore the text “beating heart of the ship” in front of all those strangers. I have never forgotten that lesson. My school became well known in the 1990s as a centre of expertise for learning about the MRM, and we presented workshops and training for our UK colleagues. There was also international interest; teachers from Tanzania and Vietnam were among those we helped train in partnership with the Dutch school. In 1993 a school in Kenya requested training, and I volunteered to go. The thing I vividly recall on my first visit was that the teachers all refused to believe that children on the videos I showed were actually deaf! Luckily I had audiograms with me, but they took some persuading. The conversational skills the MRM promoted were clearly working. The challenges of the National Curriculum in the late 1990s, gave us plenty of work incorporating what we knew to be good practice (the MRM) into the new requirements. The rigour of the new curricula was an incentive to evaluate, especially in the area of children’s written work, which for me became an area of particular interest. In 2006 a school in Vietnam requested training, and yes, yours truly was the volunteer once again! I was rather nonplussed when what I thought was to be workshops and classroom advising turned out to be an 8-day seminar presented by me to the whole teaching staff! IT incompatibility meant that all my video material went unseen, and every word I said had to be translated and then often signed, so progress was slow. In Sierra Leone, in 2016 child-centred learning is challenging to teachers used to working with classes of 50+. I find that MRM principles encourage teachers to listen to what children want to say. Van Uden calls this the “heart-to-heart”; we who work with deaf children know what he meant. Trish taught deaf children in several different settings and now works for the Ewing Foundation. I began my training in 1969 and took up my first post at the Royal Schools for the Deaf in 1973. The children wore body worn hearing aids (OL53 I seem to recall) with adult length leads (no paediatric equipment available) that looped down around their knees along with large button receivers and cold-cure earmoulds. What that meant was that personal amplification was cumbersome and largely ineffective. Nevertheless we were committed to keeping them working as well as possible and each day they were all checked – the screws in the battery compartment needed tightening every few days – and any dead items placed for replacement in a large tray that was taken round to every classroom. However – all was not lost. We had a mobile hard-wire group aid in each classroom which could provide improved amplification. That was a wooden welly boot stand on wheels with an amplifier attached and several sets of ex-RAF headphones attached for each child. If we wanted to be mobile, we used the loop to provide an improved signal – I use the word improved loosely as it was still tied to the quality of the hearing aids and the limitations of the loop system. Essentially the amplification that we could provide in those early days of my career was wholly inadequate for anything beyond a mild loss. Nevertheless, we worked our socks off to try and get the best out of what was available. I sometimes think that current technology is sold as an absolute solution and there is a danger of forgetting that we still need to check the equipment – though it is much more reliable – and ensure that it is used effectively. It is taken as a given that it will do the job for you! There were of course other challenges in achieving spoken language. One was our lack of knowledge of the development of language and the ways in which adults might support it as they did for hearing children – naturally in the home. Another difficulty was the educational setting – special schools for the deaf with a lack of natural language surrounding the children. During the 1970s hearing aids provided directly from the manufacturer became available – from Philips and Maico Windsor and soft acrylic earmoulds improved the amount of gain that could be delivered before feedback. We started making attractive harnesses and covering the mics so that babies and toddlers didn’t fill them with spilt food in the first few days! Type 1 body worn radio aids also came into use – the first that I used was the Cubex system. The child removed his or her own personal hearing aids and put on a much larger “box” which delivered sound through both microphones and a radio link. The teacher’s transmitter was equally heavy and I wonder how much of my neck problems are due to their long-term use! I took three years’ maternity leave between 1980 and 1983 and when I returned it was almost as though there had been a revolution in hearing aid and FM technology! Post-aural hearing aids were much more powerful and being used by children with severe losses and along came the Type 2 radio aid – we used Phonic Ear – perhaps it was the only one available. Earmould technology had emerged into our current soft moulds and so high levels of gain could be delivered. Nevertheless, for children with severe and profound hearing losses it was necessary to use a hard-wire group aid to deliver a good speech signal across a broad frequency range. Daily “speech/auditory training sessions” were used to promote listening and language skills and I would like to remind everyone that it is not only since Cochlear Implantation that profoundly deaf children had developed spoken language. Profoundly deaf children in the 1980s and 1990s also developed good language though their speech was never anywhere near as natural as profoundly deaf children who are implanted. It was also more restrictive since they needed to use hard-wire systems which meant that it limited the sort of activities that young children could be involved with at that time. However, the use of personal radio systems meant that during times of play and other activities the adult’s speech signal was delivered at a better SNR than previously. Technologically things were fairly static until the next big change – the advent of cochlear implantation. I remember one pupil, in the mid-1990s, who after years with hearing aids that didn’t provide – apparently – any benefit went for an assessment for implantation and the scan revealed that she had no cochleas – we couldn’t have known that before; no wonder she experienced no benefit from hearing aids! But for most profoundly deaf children implantation brought an ability to discriminate speech in a way not possible with conventional hearing aids and the consequent development of spoken language was achieved much more naturally than in previous years. However, it was not an easy path and the furore and uproar and contentious debate that surrounded the first few years was possibly worse than anything that preceded it by way of sign debate. With the improvement of technology and personal amplification systems came a change in educational placement as well as increased numbers acquiring spoken language and so the Deaf community felt threatened. Also in the 1990s came the miniaturisation of radio receivers and Phonak’s Microlink, the first ear-level receiver. It seemed that it would be a magic wand that would mean all teenagers would be happy to continue wearing a radio system throughout the secondary school years. However…. there are no magic wands in deaf education! I only rarely encountered a child with a B/C hearing aid in my career so changes towards BAHAs rather passed me by. Towards the end of the 1990s I began issuing DSP hearing aids – Widex were the first ones I used and following MCHAS they were issued – becoming much more reliable and able to adapt/be programmed more flexibly – however we sometimes forget that they are only a tool. The other new technologies were otoacoustic emissions, NHSP and early diagnosis – no longer waiting until children had failed to develop speech before fitting hearing aids, so another important technology that helped a more natural approach to the development of language in families with deaf children. Linda’s early career was spent teaching in a school for the deaf and here she describes the daily speech lessons that children received. Teaching speech in the 1970s I taught at Whitebrook School for the Deaf in Manchester during the 1970s. It was a day school for severely/profoundly deaf pupils, who were brought in by taxi. They were admitted at age 2+ (in reality as soon as they were toilet trained) and stayed throughout their primary and secondary education. About a mile away was Shawbrook School for the Partially Hearing, and pupils with a greater degree of hearing went there. The Royal School for the Deaf, Cheadle, accepted both day and residential pupils. All three schools offered oral education and were only a few miles apart. These were the pre-National Curriculum days, so schools were free to devise their own curriculum. The emphasis throughout was on language development. At Whitebrook, each pupil had a 20 minute ‘speech’ session every day. Classes were small – the biggest was eight and some had only five pupils. One hour each day was devoted to speech teaching, and pupils were withdrawn two or three at a time for an individual speech lesson. Some Teachers of the Deaf were designated ‘speech teachers’ for a year, or more, at a time. During this time, a speech teacher would have a number of pupils allocated to them (I remember having 14). The speech teacher then saw each of their allocated pupils for 20 minutes at the same time each day. The majority of pupils at Whitebrook appeared to gain little or no benefit from their individual hearing aids. These were body-worn hearing aids that were worn in a harness around their chest. Most children had two hearing aids and the aids plus leads were cumbersome and unattractive. Since they got little benefit from them, they didn’t like to wear them. In a speech lesson, we would use an Auditory Training Unit. This comprised an amplifier in a box with two volume controls, one for each ear, with a maximum output of 135dB, and a microphone on a stand for the teacher. There was a basic tone control, but no other settings. The child would wear headphones, with a boom microphone. The headphones were circumaural – they fitted right over the child’s ears, in order to prevent feedback. The inner side of the headphones was foam covered with plastic, so they could make the child’s ears very hot, especially in hot weather. The focus of the lessons was on the child’s speech production. Some children did not realise that we produce speech sounds as we are breathing out and tried to talk on an ingressive breath. Individual sounds were also sometimes produced like this so, for example, a plosive sound such as /b/ would become an implosive. Part of the training of Teachers of the Deaf was devoted to strategies to address such issues and we were taught to tear off a strip of paper and model to the child how if we held the paper by one end in front of our mouth and made a plosive sound the paper would move. As well as individual sounds, there was a focus on intonation, particularly of familiar phrases, on the grounds that it is easier for the listener to understand a phrase than individual words if some sounds are unclear. There was other equipment in addition to Auditory Training Units. At Whitebrook, the deputy head, Dorothy Neate, was keen to explore using ‘tactile vibration’ with profoundly deaf pupils (Neate, 1972). In speech sessions, some children were encouraged to use a small vibrator that could be held in their hand. This was to help them to decipher, and then use, the correct number of syllables in a word. They might be presented with two or three toys with a different number of syllables, for example a cow, a monkey and an elephant and then asked to point to whichever one the teacher said. The vibrator was used to offer additional information to hearing and vision. A small number of pupils were issued with their own individual vibrator. These pupils then wore a body-worn hearing aid in a harness on their chest, with a lead to a receiver in each ear and also a second body-worn aid that powered a small vibrator that was attached to the wrist with a lead connecting it to the aid as shown in the photo. Photo of children wearing vibrators A few pupils found it extremely difficult to control the pitch of their voice. Some used a falsetto voice and others varied the pitch in an uncontrolled way, suddenly jumping to a very high voice for one word, for example. For these pupils we experimented with using a laryngograph (an online search for laryngograph will bring up images). This involved both teacher and pupil fitting two electrodes to their throat, either side of their larynx. The teacher would say a phrase and the pupil would try to reproduce the same graph that appeared on the screen. These attempts were soon abandoned as it led to stress and frustration in the pupils as they were unable to imitate the teacher and their voices became strained. It should not be forgotten that some profoundly deaf pupils at this time did develop good spoken language and clear speech, through a combination of good use of the limited information they received from their hearing aids, good speech reading skills, good teaching and maybe an innate facility to learn language that exceeded that of others. However, for other profoundly deaf pupils, speech and language learning were extremely difficult and progress was marked by frustration and a sense of failure. Sue watched and reviewed the film Mandy, which was produced in 1952. It is a fictional account of a deaf child learning to talk and play. There will soon be a link to the film under ‘resources’. The film ‘Mandy’ was released in 1952. The main characters are Mandy, who is deaf, and her parents. It is included in the ‘spoken language’ section of the website as it provides insight into the teaching of speech to deaf children in the 1950s and 60s. Although it is a fictional account, its authenticity comes from the fact that some of it was filmed in a school for the deaf, including actual teaching of the pupils. (The film acknowledges Clyne House Manchester and the Royal Residential Schools in Manchester.) It shows groups of children at their lessons and, while these had to meet the demands of the plot, the activities we observe could only occur with the cooperation of the children. The film is based on a book ‘The day is ours’ by Hilda Lewis, a novelist and children’s author. Her husband was Professor Michael Lewis whose research was into the education of deaf children. He was Chairman of the group that produced the report ‘The education of deaf children’ also known as ‘The Lewis Report’. The film ‘Mandy’ received many accolades and was the fifth most popular film at the box office that year. It received the Special Jury Prize the 1952 Venice film festival. We first meet Mandy when she is nearly two as her mother becomes increasingly worried about her progress. She is not developing speech like other children her age. But friends reassure Mandy’s mother telling her some children talk later than others. There are many attempts at home to test her responses to sound and ultimately a tray dropped behind her, to which she does not respond, confirms their suspicion she is deaf. She is taken to see a specialist. To modern ears the words spoken by the specialist seem cruel “The actual physical structure of the ear is perfect. There’s no question of an operation. It is one of those interesting cases where the auditory nerve has failed to develop, and this is what we all a congenital condition”. Mandy’s mother summarised the situation as she saw it “Everyone told me there was nothing to be done. Mandy would never hear; she would never be able to imagine what sound is like so naturally she would be dumb too”. Initially she is looked after at home, but her mother becomes increasingly concerned at her inability to communicate even with her family. She looks at schools for the deaf but none seems suitable. Eventually, though, she finds a school which offers some hope and aims to teach children to talk. However, it is in Manchester, far from their London home. On her first visit she was impressed to see deaf children communicating. After looking around the school the mother says “I saw children younger than Mandy and deaf like her but they could speak. They’ll grow up to have some place in life. They’ll get a chance to live like normal people, not shut up like Mandy is”. On Mandy’s first visit a child approaches her and offers a plasticine necklace. After some hesitation Mandy takes it and then goes off with her to play with the other children. Mandy enters the school as a boarder but does not settle. She does not play with other children, she does not eat, she cries at night and gets distressed in class. We observe one class where the teacher holds up two model animals and asks questions such as ‘Which one is the donkey?’ ‘Which one is the tiger?’ All the other children take their turn enthusiastically, but Mandy is unable to do it and, stressed, runs to the corner of the room. The contrast in all these scenes is between Mandy’s lack of involvement and the other children who are happy, interacting and joining in. Interestingly, no signing is apparent in the film and also no child is shown with a hearing aid. It is seems that Mandy’s problems arise because she joined the school when she was older and this is resolved by Mandy becoming a day pupil rather than a boarder. With additional sessions from the headmaster, Mandy becomes well integrated into her class. There is a particular critical session. In this lesson, each child goes up to the blackboard with a toy, for example a doll, points to its word eg ‘baby’ and says the first letter ‘b’. While most children can do the task, Mandy can only make the lip pattern but she does not make a sound. The teacher brings out a balloon and lets Mandy feel it while she makes continuous ‘b’ sounds. Mandy holds the balloon to her face and keeps trying but cannot work out what to do, continually producing the correct lip patterns but no sound. In the end she becomes frustrated and runs to the corner of the room and throws a plate to the ground. It breaks and she screams. Immediately, the teacher exploits the scream and joins her in throwing crockery to the floor and screaming. She then re-introduces a balloon and lets Mandy feel her the vibrations of her screams on the balloon. Eventually Mandy works out what she needs to do and is able to make the sound. Mandy is shown as becoming more and more cooperative in the various activities at school. The class is shown in a variety of situations, including acting out a story where Mandy is asked to be a tree; she understands what she has to do and enjoys being part of it. However, learning to speak is presented as the more difficult task and much of the teaching is based on repetition of single sounds which are later combined into words. Mother and Mandy also practise sounds at home. Eventually a breakthrough occurs and she says ‘mummy’ made up of mum..m..y. The final climax of the film draws on a theme that has occurred throughout the film, that of children playing. In the early part of the film we are shown Mandy looking out of the window at hearing children playing, yet she is unable to join in. When her mother makes the first visit to the school she comments on how much she likes seeing the deaf children all play together. This is in contrast to an episode which comes very soon after when Mandy and her parents are in a park. She wanders off and a boy and girl try and get her to play. She gets frustrated as she does not understand the game and ends up attacking the boy. In the final scene, she is again watching hearing children play and goes up to join them. They ask her her name and hesitatingly she says ‘Mandy’. Sue describes the correspondence course that the John Tracy Clinic offered to parents of young deaf children. John Tracy Clinic Correspondence Course for Parents of Preschool Deaf Children was a correspondence course used by some parents of preschool deaf children in the UK in the 1960s and 70s. The course was based on the work of the John Tracy Centre in the USA, which was set up by Louise Tracy, wife of Spencer Tracy, based on their experiences with their son John who was diagnosed as deaf in 1925. It became available as a correspondence course in the UK in 1954 and a bound version of the units for professionals was published in 1968. The exact numbers who followed it in the UK are not known but in an interview study I carried out with parents of young deaf children in 1970-71, 15% knew about the course and most of this group had tried it. (Reference: Gregory, S. (1995) Deaf children and their families. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. Previously published as ‘The deaf child and his family. London. George Allen and Unwin, (1976)). It was a correspondence course in 12 parts which took a totally oral/aural approach. As one section was completed, parents sent back a report detailing their progress and got feedback from the clinic on their report and the next part of the course. It offered a great deal to families in terms of information about deafness, advice on communication, suggestions for toys and books to buy, descriptions of developmental stages, discussion of behaviour issues and, towards the end, on thinking about schools. It was a compendium of ideas and resources which many parents appreciated. There is too much in the course to describe in detail here, so I have chosen to discuss a small part of the suggestions in the first four lessons, focussing on those concerned with language and communication. The course began with basic information such as emphasising that for a child to be able to lip read he needed to be able to see the mother’s face. (Author’s note: In keeping with the conventions of the time, the course always refers to the child as ‘he’ and addresses itself mostly to the mother with an occasional aside to the father describing how he too could be involved.) The mother was advised to take every opportunity possible to talk to the child and many suggestions were made as to the sorts of things she could say. A ‘tear-out page’ to put up gave ideas for phrases she could use throughout the day, for example: The message of this section was ‘Speak every time your child looks at you’ (II-22) Alongside an emphasis on talking at every opportunity and encouraging the child to watch the face, in Lesson III the course introduced a more structured approach to speech – ‘Your child’s first lip reading word’. The basic idea was to establish particular words one at time, not introducing a new one until the child could easily recognise the first one. The word had to be something that could be talked about every day and they suggested ‘ball’ as a possibility. Numerous ways for introducing the word ‘ball’ into everyday life were described. The parents, of course, could choose another word. ‘This first lipreading word must be repeated again and again until your child can lip-read it in any logical or appropriate situation. You say it and say it and say it, day in and day out, in connection with the object it represents’ III-9 Lesson IV reinforced the child’s recognition of the word ‘ball’ but went on to discuss developing the child’s own spoken language by introducing a word that the child would be encouraged to say – the first ‘expressive word’. The course suggested the word ‘off’, which had already been introduced as a possible word to lip-read. It was seen as useful for the development of expressive language because ‘strangely enough the words that children first use are seldom the names of objects’ (III-10). It was suggested that saying ‘off’ frequently in a number of contexts could encourage the child to attempt to say it himself. It is important to recognise that some of these ideas might seem dated from a 21st century perspective, and even not good practice, but at the time they were radical and gave a structured approach to parents in a way not easily available elsewhere. There were some difficulties with the course even at the time. Some of these were recognised and discussed in the introduction to the material. For example, as it covered children from two years to six years not all activities were suitable for all children and not all children could be expected to progress at the same rate. This is pointed out and discussed. However, in addition, the course was very positive in its outlook and for parents with a child who did not co-operate in the activities, did not enjoy social games, or was very active most of the time, the course may not have been as effective and thus such parents may have felt discouraged. Parents of deaf children with additional difficulties could also feel excluded. Because it had a ‘can-do’ philosophy, there seemed to be little support for families and children who could not and did not make progress. It did make certain assumptions about the life of the family, in particular that the mother had a great deal of time to spend with the deaf child. Little attention was paid to other children in the family and how they might have been involved. There were very many illustrations throughout but few show anything other than a mother (or very occasionally a father) and a deaf child. Where another child was shown, it was to illustrate the point that a deaf child must have opportunities to play with others and it was not about involving other siblings in activities. Overall though, it has to be recognised that this course was a significant tool, gave a wealth of advice and information on many aspects of deafness and provided a structure for parents in interacting with their children. End note The Elizabeth Foundation has now developed their own materials based on those of the John Tracy Clinic. They are currently in the process of replacing the hard copies with online lessons. They are similar to the John Tracy Clinic material in that parents work through them at their own pace and then receive individually tailored advice. The details are available on their website http://www.elizabeth-foundation.org David Braybrook MA, FRSA reflects on changes in deaf education since the 1960s. He considers the impact of this on the teaching of spoken language. David is a Consultant Specialist in Special Educational Needs and has worked in this area for 25 years. In August 1966, I completed the one year Teacher of the Deaf course at Manchester University and I was looking forward with some trepidation to starting teaching in Surrey at Nuffield Priory Secondary School for the Deaf. It is hard now to recall, and I imagine harder for recently qualified ToDs today, to conceive of the structure, the beliefs and methodologies of the profession at that time. The majority of deaf children were in large residential special schools in which they were enrolled at the age of five or earlier. The Royal Schools at Manchester, Margate, Preston, Exeter, Derby together with Northern Counties School in Newcastle were large non-maintained special schools and were very significant powerful institutions which sat alongside the two selective special schools Mary Hare Grammar School for the Deaf and Burwood Park Secondary Technical School for Deaf Boys, as well as the Jewish School for the Deaf in London and St John’s RC School for the Deaf and a small number of LA day schools. A number of schools for the partially deaf that were created after the Second World War subsequently became the partially hearing special school provision at Needwood School in Staffordshire, Birkdale School in Lancashire, Tewin Water School in Hertfordshire and Ovingdean Hall School in Brighton. The profession of teaching deaf children was routinely referred to as the “world of the deaf” and in reality had limited connection with schools in the maintained, mainstream sector and educational thought and practice. The work was seen as necessarily different as deaf children “needed to be taught language” and in most settings “taught to speak”. This task dominated the educational agenda. Most of the teaching was in the oral tradition but audition was not a reality in the sixties for the vast majority of children as Medresco hearing aids, which evolved from the technological advances in the war, did not benefit those children with more severe or profound hearing loss. At this time, many children with profound losses (65/70 dB or more) were not diagnosed until four or five years of age. The vast majority of Teachers of the Deaf in the sixties were in-service trained and many of them had taught in the same school for forty plus years. They often came to the work from family backgrounds of deaf parents, relatives or siblings. However, change was afoot in the late sixties and early seventies. The potential of units, first created in London in 1907 was becoming evident and schools such as Woodford School in Essex and Birkdale School in Southport were exploring the potential of a more auditory based oral practice and by the late sixties the first commercial hearing aids began to exploit more effectively the residual hearing of deaf children. Courses for training Teachers of the Deaf other than the one in Manchester began to emerge in Oxford in 1969, Scotland, London, Birmingham and Hertfordshire in the seventies and Leeds in 1992. Research in America, Russia and the Netherlands into early language acquisition, linguistics and sign began to question how a first language is acquired and what is needed in the learning environment for deaf children to become competent and effective communicators. The acceleration of change strongly influenced by academic and action research and aided by audiological, technological and medical advances resulted in a greater focus on academic learning, access to a broad and balanced curriculum and a greater appreciation of the potential of deaf learners changed the quality of the schooling and the lives of deaf children and their life opportunities. Fifty years ago, young people who were born deaf were offered very limited job opportunities and their immediate predecessors in the forties and fifties were seen as being well placed as cobblers or carpenters if young men or laundry workers or in service if they were young women. Now through societal change and legislation we have young people who are deaf in a wide range of employment – creative, professional, practical, skilled and unskilled. Society and media acknowledge and have an understanding of deafness which was not in existence in the early 60s when childhood deafness was linked in the minds of many to “dumbness” and pity for them as handicapped children. Challenges remain, many to my mind linked to an increasingly fragmented educational system, which makes ensuring equality of access to specialist support for deaf children through their school and early adult lives a dilemma for local authorities and for the profession. The reality of the incredible changes for me is encapsulated in meeting deaf children and young people who have profound hearing losses but have age appropriate language, are competent communicators in spoken or sign language and are achieving academic outcomes which were unimaginable in the sixties. BATOD and its members together with the voluntary organisations should feel rightly proud their part in promoting and navigating and implement such major change and development across the fifty years.