Spoken Language and the Education of Deaf Pupils

An overview by Linda Watson

The period from 1960 – 2010 encompasses an interesting era in the teaching and use of spoken language (at that time referred to as oralism) in deaf education. In the 1960s, it was the predominant approach used with all deaf children. Gradually this changed, with the introduction of Total Communication (ie signs for key words used alongside speech) and then sign bilingualism. Alongside these developments, there were changes in the way that spoken language was taught (either directly or by ensuring optimal conditions for the child to learn) and advances in technology in the form of digital hearing aids and cochlear implants that facilitated the development and use of spoken language for more deaf children. There were also changes in practice around educational provision that further influenced the situation.

Teaching speech and language

In the 1960s and 1970s, great stress was placed on the importance of teaching speech and language – where ‘speech’ was used to describe the sounds, including such aspects as breath control; the way sounds were formed; rhythm; stress; pitch; volume, and ‘language’ referred to the words used – sentence structure; vocabulary; grammar etc. As teachers of the deaf, the maxim was ‘every lesson is a language lesson’ and there was always a focus on promoting language, to such an extent that the subject (geography, history) could take second place to the emphasis on language. Speech was taught and practised incessantly and most deaf children would have a daily individual session of speech teaching in addition to the emphasis in class. There was a stress on using children’s residual hearing but hearing aids were body-worn and cumbersome and offered little or no benefit to many deaf children. In speech sessions, Auditory Training Units were frequently used.

Other schools used different approaches, for example St John’s School for the Deaf, Boston Spa, used the Maternal Reflective Method, and sent teachers to train at St Michielsgestel in The Netherlands. This approach built upon the personal contributions of deaf children, with the addition of the written form. For example, on a Monday morning there might be a news session and a child might say: “Saturday I go shop Mummy”. The Teacher of the Deaf would write this on the board and invite the rest of the class to talk about the sentence. This initial contribution was initially called ‘the deposit’, but soon became referred to as ‘the reading lesson’, a term that more accurately reflects the approach with its emphasis on the written word. The class would then work on the sentence and develop it to become: “On Saturday I went to the shops with Mummy”. This more complete version of the sentence would be recorded and returned to during the course of the week to remind the pupils. Whatever the example, the emphasis was on taking the child’s contribution as a starting point for a conversation and lesson.

A move away from spoken language

There were several parallel developments in the 1980s and 1990s. One was advances in technology, discussed below, whilst another was the increased use of sign and the introduction of sign bilingualism. Whilst this is discussed in more detail under that name on the website, of interest here is the fact that when sign bilingualism was introduced in some areas there was no attempt to teach or encourage spoken language – the term ‘bilingual’ referred to the use of BSL and the written version of English rather than spoken.

Advances in technology

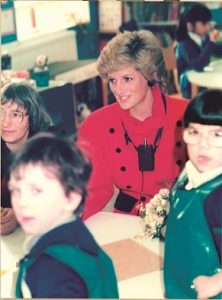

Advances in hearing aid technology meant that many more deaf children could have access to sound, and developments in postaural hearing aids meant that they were now suitable for children with more significant hearing losses. FM systems (at the time called ‘radio aids’) came into widespread use, transforming the listening experience for deaf pupils, particularly in mainstream situations. The earliest FM systems were body-worn and were worn in place of an individual hearing aid as they were intended to amplify sound like a personal hearing aid as well as receive the transmitted radio signal. The Phonic Ear was one that was widely used and the deaf child wore the receiver unit in the centre of his/her chest, with a lead to each ear that attached to a small receiver and earmould. There were two microphones on either side at the top of the receiver unit that needed to be kept clear – but in practice they seemed to attract stray bits of food, drink and play dough! The transmitter, worn by the teacher or parent, was also quite large and heavy and worn round the neck. Then a second generation of FM systems was introduced, called Type II systems, that were used in conjunction with the pupils’ own hearing aids. These were still quite bulky, but did enable deaf pupils in mainstream classes to hear much more clearly what the teacher was saying, provided that the teacher wore the transmitter correctly. The photos show an early Type 11 radio aid from Connevans and Princess Diana wearing a later Connevans Type 11 transmitter.

We are grateful to Connevans for providing these photos.

One consequence of the accurate assessment of deafness was that the site of lesion (ie where the hearing loss occurred in the hearing pathway) was established. Whilst in the majority of cases of permanent childhood hearing loss the reason for the deafness lies in the cochlea, on occasion a deaf child has been shown to lack an auditory nerve. This means that neither a hearing aid nor a cochlear implant will offer access to sound, a fact that will influence any decision on the appropriateness of continuing with an oral approach.

Greater understanding of how children learn language

At the same time, greater understanding of how hearing children learn to talk led some Teachers of the Deaf to begin to develop approaches that incorporated aspects of this understanding into their teaching. The widespread use of video recorders made it easier for teachers and parents to track deaf children’s language development.

In 1981, a group of Teachers of the Deaf and course providers met and formed the Natural Aural Group (NAG) . The name reflects the emphasis placed on following the way that parents interact with young (hearing) children to promote their language development, hence ‘natural’ and the stress on listening, hence ‘aural’. Natural auralism developed as a teaching approach used with deaf children. Its basic principles included the maximum use of residual hearing, so hearing aids were always kept in good working order and worn consistently. Parents and teachers were encouraged to talk to deaf children at normal speed and not to exaggerate their lip-patterns. Rather than attempting to teach language by following a language scheme as described above, language development was encouraged through play and conversation. Natural gesture was encouraged, but no formal signing was used and lip-reading was neither encouraged nor discouraged – the view was that a deaf child would look to speech read if they needed to. However, gaining the child’s attention and ensuring good listening conditions were strongly encouraged. Very soon parents of young deaf children wishing to follow the approach were offered the opportunity to attend summer schools with their deaf children.

This was an era when Local Authorities were able to specify what approach they offered for teaching deaf pupils and parents frequently moved house in order for their child to be educated in an LA that had adopted natural auralism. Teachers of the Deaf, too, were attracted to working in LAs that espoused their own favoured philosophy and frequently moved house to work in an area.

The original group was drawn from different educational settings, including units, peripatetic services and schools for the deaf. Morag Clark, who was the head of Birkdale School for Hearing-Impaired Children in Southport from 1976-1986, produced a series of teaching packs that included videos, based on the use of interaction and also wrote a book.

The term ‘natural auralism’ became widely adopted and over time it was used to describe situations or teaching approaches that did not adhere to its principles – thus one teacher described her approach as ‘natural auralism with a bit of sign support’. Natural auralism definitely served to move oral teaching of deaf children away from the structured, formulaic approaches that had previously been used and towards an approach that promoted language development in a similar way to how hearing children’s language develops. Some professionals criticised natural auralism for being ‘laissez-faire’ as they perceived the approach failing to offer the support that many deaf children needed. However, skilled practitioners of the approach were constantly assessing and monitoring deaf children’s progress and acting on their observations, whether by checking the adjustment of a hearing aid to provide a child with access to a particular speech sound or providing opportunities for the child to be exposed to certain vocabulary.

Other approaches

Two other approaches to promoting spoken language are cued speech and Auditory Verbal Therapy (AVT). Cued speech was invented in the US by Dr R. Orin Cornett. On the Cued Speech Association’s website, it describes it as follows:

“Cued Speech is a visual mode of communication in which mouth movements of speech combine with “cues” to make the sounds (phonemes) of traditional spoken languages look different.”

The aim is to assist deaf children in learning to speak, by helping them to differentiate between sounds with similar lip patterns. It has never been widely adopted in the UK, although it is popular in some other countries, eg France. Those who favour natural auralism do not accept it since it requires the child to watch and listen rather than simply listen and involves the use of cues, which are similar to signs, whilst for those who are using sign it is not acceptable since it is not possible to cue and sign simultaneously.

Auditory Verbal Therapy is, as the name suggests, a form of therapy for deaf children. It promotes the development of spoken language through listening, without any use of visual support and aims to prepare a young deaf child to enter mainstream school. It can only be delivered by a qualified Auditory Visual Therapist, although some Teachers of the Deaf have adopted elements of the therapy, especially acoustic highlighting whereby the most important word or phrase in a sentence is stressed by saying it more slowly, whispering it or emphasising it. Some cochlear implant centres in the UK offer AVT to parents following their child’s implant in the belief that deaf children who receive a cochlear implant may not automatically develop their listening skills and AVT is seen as a way to assist deaf children to learn to listen post implant.

Changes in educational provision

Alongside these developments in technology and teaching approaches, there were many changes in educational provision. The trend towards educating deaf pupils in mainstream schools (see the section on the website with that title) meant that increasingly deaf children were educated alongside their hearing peers, initially mostly in Partially Hearing Units. Whilst the decision for each individual deaf pupil was made on the basis of several factors, some Teachers of the Deaf (the author included) visited local PHUs and observed deaf pupils with seemingly very similar profiles in terms of hearing loss etc who were developing much better spoken language than pupils in special schools. This led some Teachers of the Deaf to determine to ‘do oralism better’ rather than to rush to introduce sign language and thus, for us, served to reinforce a belief that more deaf children could develop good spoken language and clear speech.

Another change in educational provision came with the introduction of the National Curriculum. Whilst initially it was possible to exclude deaf pupils from the need to follow the NC, this was not seen as in their best interests and so schools for the deaf needed to provide a full and balanced curriculum. It was now important to focus on the curriculum and, whilst language development was still seen as important, it was no longer allowed to dominate the curriculum.

And so it continues…

By the end of the period under consideration, Newborn Hearing Screening had been introduced, leading to earlier intervention and support for deaf babies and their families and, for many, fitting of hearing aids and assessment for cochlear implantation at a much younger age. There is no doubt that for many severely and profoundly deaf children these developments are leading to improved access to speech sounds and development of spoken language.