My life and deaf education

This section differs from the other sections of the website as, rather than being topic based, it allows contributors to take an overview of a number of different aspects of deaf education over a period of time. It is a different but an important way to look at the changes experienced between 1960 and 2010, the period covered by the website.

It arose because in the early days of the website, we received two pieces which went beyond a specific area but provided a valuable and rich account of the period. We were able to add to this later, through articles submitted for the ‘40 years on’ edition of the BATOD magazine published in November 2016.

Further contributions to this section, looking at this period as a whole, will be very welcome.

Index

- The rather unusual but successful education of my sister Rachel. Betsy Chaloner trained to be a Teacher of the Deaf in Manchester with the Ewings. Her first post was at the Old Kent Road School for the Deaf and later she was the deputy head of a school for the deaf.

- Seventy years with deafness. Jennifer Sherwood also trained at Manchester. Before she retired, she was a Teacher of the Deaf, an advisory teacher working with preschool children and their families, and an Acting Head of a School for the Deaf.

- Forty years on. Elizabeth Andrews trained Teachers of the Deaf at Oxford Polytechnic and the University of Birmingham and later worked at the RNID, and at the Department of Children, Schools and Families.

- Changes and challenges in deaf education. Ted Moore is a former president of BATOD and former head of Oxfordshire Sensory Support Services.

- Deaf education from the 1970s to 2016; a personal journey and recollection. Sue Lewis is a qualified Teacher of the Deaf and has spent many years training Teachers of the Deaf and advising local authorities. She currently works as a senior advisor and inspector.

- Signs of the times. Miranda Pickersgill was for many years a Teacher of the Deaf and head of service. She is a former CEO of CACDP (now Signature).

- Living in interesting times. Sue Gregory is a former Reader in Deaf Education at the University of Birmingham and now coordinates the deaf history section of the BATOD website.

- Reflections on the inaugural meeting of BATOD in 1976. David Braybrook is a consultant specialising in SEND work (0-25 years).

- Battling for BATOD. Ann Underwood held various positions in BATOD over many years. She was President between 2008 and 2010 and is now the BATOD Foundation Chair of Trustees

- Reflections. Pauline Hughes was for many years a Teacher of the Deaf and head of service and was president of BATOD from 1995-1997. More recently she has been. CEO of the Ewing Foundation

- Retirement speech at leaving party (July 1992). Shirley Aston taught for a short period in mainstream schools before becoming a Teacher of the Deaf. She has wide experience in schools for the deaf and as a peripatetic teacher.

- Personal Journey. Sue Archbold was until recently Chief Executive of the Ear Foundation and, prior to that, Coordinator of the Nottingham Paediatric Cochlear Implant Programme.

- My life and deaf education 1942-2017. Sandra Dowe Teacher of deaf children, Head of Hearing-Impaired Service, Honorary National Secretary BATOD 1988-1992, Executive Officer Deaf Support.

- Stepping-Stones to Teaching: historical context on disability access from a personal perspective. Mabel Davis is a former Head of Heathland School for the Deaf, a former representative on the National Disability Commission of the General Teaching Council and a Trustee of the RNID.

Accounts 1 and 2 are by Betsy Chaloner and Jennifer Sherwood. Both these authors were born in the 1930s, are siblings of deaf people, and both became Teachers of the Deaf. Thus they are able to describe, from first-hand experience, developments in deaf education over a long period of time.

In the following two accounts, 3 and 4, Elizabeth Andrews and Ted Moore look at the changes in deaf education over the past 40 years. Ted Moore, in describing his long experience as a Teacher of the Deaf, looks at the various terms that have been used to describe deaf children and how changes brought about by various Education Acts have affected deaf education. Elizabeth Andrews describes the many changes since she began work as a Teacher of the Deaf in 1978 and how there is still much to do in deaf education.

Sue Lewis, Miranda Pickersgill and Sue Gregory in accounts 5,6 and 7 provide varying views of the approaches to language in the education of deaf pupils. Sue Lewis describes a long career with a particular interest in speech and language. She discusses the many changes that have taken place and how they have impacted on deaf children’s development. Miranda Pickersgill talks of her experiences in deaf education from a time when sign language was not seen to have a role in the education of deaf children to the development and significance of sign bilingualism. Sue Gregory describes how she came into deaf education through a series of accidents which resulted in an interesting career focussing on the language and communication of deaf children.

Both David Braybrook and Ann Underwood include a consideration of the development of BATOD in their accounts. In account 8, David Braybrook reflects on the nature, speed and extent of the change in BATOD over the past 40 years, from its inaugural meeting in 1976. In account 9, Ann Underwood describes her career as a Teacher of the Deaf, particularly her work with young people and the changes she has seen in this area. She also looks at the role of BATOD and her contribution to this.

In accounts 10 and 11 Pauline Hughes and Shirley Aston look back over a period of 40 and 50 years involvement in deaf education. They are able to give vivid accounts of life before even radio aids and other technological aids, as well as in Shirley’s case throwing a new light on peripatetic work.

In account 12 Sue Archbold looks back on a career in deaf education focussing on her experience in the area of paediatric cochlear implantation from working with the first child to be implanted in the UK until the present.

In account 13 Sandra describes her life, firstly as a teacher and then as a teacher of deaf children. Her understanding of the issues is informed by her relationship with her maternal grandmother and grandfather, both of whom were deaf and fluent in sign language.

In account 14 Mabel Davis looks back on a long career in deaf education from a particular perspective having been born hearing and becoming deaf through meningitis. She describes the barriers she faced in becoming a teacher of the deaf, and the influence of her experiences on her teaching and later as head of a school for the deaf.

Knowing that, on return to India, help for Rachel would depend wholly on her, my mother sought help from Dr and Mrs Ewing in Manchester. I have her notes from that time and they are very reminiscent of my own time training in Manchester twenty five years later. The approach was, of course, totally oral, with any signing, or even gesture, completely forbidden! The Ewings certainly gave my mother a very thorough grounding on how to help Rachel. How to talk so as to make lipreading as easy as possible (light on my own face, no exaggeration etc.). On phonetics – breath and voiced sounds and how to teach them. On reading and how to start this with Rachel. My mother was also encouraged to make use of any residual hearing Rachel had by talking into her ear – no hearing aids in those days.

And so back to India. Of course, I can’t remember the teaching that went on at that time, but my mother must have worked really hard with Rachel. I don’t personally remember ever having any difficulty talking to Rachel. She was always my big sister who was able to do things I could not do – including reading, which from that time on became one of her greatest pleasures.

In December 1936, my parents had to return to England, and it was thought that perhaps Rachel would benefit from going to a school for the deaf. However, on visiting Margate school my mother was absolutely horrified and so for a while continued to teach Rachel herself.

I remember Rachel joining my mainstream nursery class. At the end of the afternoon we sat on the floor for a story, so her lipreading must have been pretty good by then!

After two years at a small private school for deaf children where she did not seem to make much progress, my father moved to be minister at a new church, and mother again taught Rachel at home. I remember the daily speech sessions with repeated rhymes to practise difficult speech sounds, for example:

- How tall am I Granny?

- Please will you measure.

- What! Measure my treasure?

- With pleasure with pleasure.

Because my grandfather was able to help finance our schooling, during the war years I went to a local private school and when she was ten Rachel joined me there. She was very popular – very jolly and full of fun. She was able to keep up well in lessons with me available if she missed anything.

We remained together, though in different classes, when we moved to a secondary boarding school where children were taught in small classes. Here again, being a real extrovert, she made good friends and generally fitted in very well. I remember her making up exciting stories and telling them to the rest of the dormitory after lights out! She enjoyed acting in the school plays and taking part in other school activities.

She was not a person to give up easily. Once, in the annual inter house competitions, one of the ways to gain points for our house was to jump or dive from the top diving board. Rachel was afraid of heights, but shaking with fear, she climbed up and, with typical grim determination, stood looking down with horror, and then jumped!

She went on to take her “School Certificate” as it was then, and though I can’t remember what other subjects she took, I know she got credits in English language and literature.

After leaving school she went to technical college and did courses in typing, cooking and child care, continuing to read voraciously whenever she could. I have a mental picture of her doing the washing up with a book propped behind the taps!

She then got married, as she had always wanted, and had five children, sadly dying of cancer before they had grown up.

I went on to teach deaf children, at first in the Old Kent Road School for the Deaf. I was, like my mother before me, surprised and shocked by the standard of the children’s language levels, lipreading ability and speech. However, I was very lucky to get enormous help from the school’s great head teacher, Molly Johnson, so that I had a good head start when I went to Manchester for my further training with the Ewings.

After years of lectures, teaching practice, auditory training, taking lessons in front of our fellow students (what a nightmare!) and taking individual children for speech lessons, I returned to Old Kent Road to start my career as a teacher of deaf children in earnest.

I am very much aware that my mother was very fortunate to be able to give the time to teaching Rachel herself, quite impossible for most parents these days.

Now that there are cochlear implants, better hearing aids, the option of using signs and all the different school scenarios, parents have difficult choices to make. Whatever they decide, it is certain that their input, providing meaningful communication at the earliest possible stage, remains vitally important if their children are to grow up to be competent, confident adults like my dear, jolly, happy sister.

In November 1944 my only sister was born, the youngest of 5 children. In 1946 she was still not walking although she sat up and crawled at the normal time. She said a few words. She was diagnosed as a spastic diplegic. This was the early days of the Spastic Society. Her delay in walking and talking was attributed to her cerebral palsy. My mother arranged for her to go to a Rudolph Steiner Nursery when she was about 4, where she was very happy, but she could not stay there after the age of 6 since she was still not talking. Only gradually was the possibility of deafness mooted. She was found to be profoundly deaf. We had all, including my mother, had German Measles when my mother was in the early stage of pregnancy. The link with deafness and rubella had only just been made.

Things moved pretty fast then. My mother and sister had an interview in London and my sister was offered a place at the Royal School for Deaf and Dumb Children in Margate and went into the Opportunities Class in the Homes. I think she was nearly seven years old. Her very first teacher was Doreen Woodford. My mother joined the Deaf Children’s Society and I remember going with her to a talk in London by Arnold Bates about Mary Hare Grammar School. At that time the DCS, as it then was, produced a magazine ‘The Silent World’, a title reflecting the understanding and ethos of the time. I later met the little girl, whose photograph was shown on the front of each copy, on teaching practice. My mother became involved with the St. Albans Diocesan Mission for the Deaf and used to help with teas and hold tea parties in our large garden. The Rev. Percy Corfmatt was in charge and we got to know Canon Sutcliffe quite well. In those days services for the deaf were very church orientated. My sister made many very good friends at Margate, friends she kept up with for the rest of her life. She played a full part in school life and in spite of walking difficulties went camping with the Guides on a number of occasions. She was there under the headships of Mr. Swayne and Mr. Pursglove. I left school and went to Bedford College for Women, London University, where I read History. Afterwards, instead of doing a PGCE I decided to train to be a Teacher of the Deaf at Manchester University. I shall never forget the comment of one of my former teachers: ‘What does a clever girl like you want to do that for? After all, the deaf only need to sit at the front of the class.’ The OL56, the first transistor hearing aids had just come into existence and was seen by many lay people as a cure-all. These sturdy body worn hearing aids replaced the heavy cumbersome aids with batteries in leather cases, which were difficult for my sister to carry around.

I was interviewed by Professor Alexander Ewing in a hotel off Oxford Street, London and offered a place at the Department of Education of the Deaf. I remember he stressed the importance of oralism. It was the age of ‘New Opportunities for Deaf Children.’ I knew, however, that the adult deaf and many deaf children outside the classroom signed to communicate with one another. My sister had taught me signs and told me the names of many of her friends. In spite of the increased opportunities with transistor hearing aids for some children, the teaching of speech by teaching how specific sounds are physically produced rather than making the most of residual hearing was an important part of the curriculum.

As well as short visits to schools and partially hearing units I spent two weeks in a Secondary Modern School in a poor area of Salford, a real eye-opener in many ways. The whole of the Spring Term was spent on teaching practice, the first half at Mary Hare Grammar School, the second half at Preston School for the Deaf, two very contrasting placements. At Mary Hare one of the Staff slipped on the ice, broke her arm and I took her classes for several weeks – an interesting experience. Quite a number of the staff at Mary Hare were not qualified Teachers of the Deaf or were currently undergoing in-service training. They had the cream of deaf children and/or children successful orally. Yet, they were very critical. Whilst at Mary Hare I was invited to sit in on a discussion about candidates for selection and was amazed at the prejudice against children from a school where it was thought signing was predominant outside the classroom, namely Margate. I recognised the names of some of the children! None of them was offered a place. At Mary Hare also I met one of the children featured in Ewing’s ‘New Opportunities’ and her future husband. I was later to meet her again as a young mother with a young daughter, also deaf. The other half of the term was very different in Preston. There I was very much ‘the student’. The teacher split the class in two. I had one half of the room and she the other. There was an invisible barrier between us. On completing the course I was offered a place doing research in the Department, but I wanted to get out into the world of work and Manchester in the 1950s was a smoky, foggy city! I obtained a job at Nutfield Priory School in Surrey under Sam and Joy Blount, and Norah Browning was Deputy Head. There was a sort of affinity between us. We all had personal connections with the deaf. All three had previously been at Margate. Sam Blount was full of enthusiasm for his ‘new’ school, for the possibilities of a greater oral emphasis. He brought with him ‘diagrammatical English’ from Mr Swayne at Margate – a system which helped to overcome problems with sentence structure. He managed to introduce CSE exams for his pupils, obtaining permission to create a syllabus appropriate for the deaf. Every night the children came into the Hall to watch the television news. The teacher on duty had to give a spontaneous commentary to what was said. There were no subtitles for the deaf then. Once I remember there was a power cut and it was extremely difficult holding a large lantern so that my lips could be seen and at the same time giving a commentary. Plus points were given to encourage oralism and minus points for too much signing. Hearing aids were valuable items so were not necessarily worn outside the classroom in many schools for the deaf. Commercial hearing aids were just coming in and a group of children in my class living in the same local authority were issued with identical hearing aids and probably with identical settings too. The understanding of audiology and differences in hearing loss were still in their infancy. Integration in the local community was encouraged and I took a group of Nutfield Priory children to the local Guide Company and ended up running it! On Saturday mornings we walked into Redhill to the Pictures and back again in time for lunch. On Sunday afternoons we took the children for a walk. If there were under 20 children only one member of staff was required. I may have the number wrong but I do know that nowadays the number of any children, let alone deaf ones is far, far lower!

After Nutfield I went to Heston School, close to Heathrow airport. When in the dining hall it sounded as though planes were coming through the roof! Only one room was sound proofed. The school day was shorter because of the children arriving and departing in a fleet of taxis. There was less opportunity for incidental learning. On the other hand some of the children were able to join sports clubs or play with hearing children in the neighbourhood and had the benefit of home life.

My sister left school at 16, the school leaving age for children in special schools, at that time. After a brief spell at a firm making hearing aid leads my mother negotiated her a job at Ovaltine’s where she was to remain for her entire working life. I think she was a packer or something similar. In the early 1960s there were few opportunities for the deaf school leaver to have further education or go to College. Fortunately, she was a good lip reader and one or two older women took her under their wing and she was a very happy and loyal worker. Socially, she kept up with former school friends and joined Breakthrough, where she made friends who had attended other schools for the deaf, partially hearing units and also mainstream schools. After she was made redundant, when new health and safety regulations led to many deaf people who had worked losing their jobs, she became active in local social clubs for the deaf. She married.

After teaching at Heston I also married and had three children, so I was out of deaf education for about ten years. During this time I maintained my membership of the NCTD and went to the occasional meeting. On two occasions whilst the children were still young I was told there was a vacancy at a PHU in the vicinity and asked if I would take it on, but the children were still too small and I was about to move. When my youngest child started school I obtained a part-time job running an ‘Opportunity Class’ for children with special needs. Almost simultaneously as a result of a rubella epidemic in the area there were seven hearing-impaired children, whose parents needed support. I was asked to step into the breach, as an Advisory Teacher of the Deaf. So began more than twenty years of working with pre-school hearing-impaired children and their families, advising teachers in mainstream schools on the needs of the hearing-impaired children in their care. Although I had started with the pre-school children alone it wasn’t long before I had a case-load from pre-school to College. The first post aural hearing aids, the OL67, had just come in. Auditory Training Units were initially an essential part of my equipment. I met some wonderful mothers who coped admirably with difficulties. I saw sadly a number of broken families with fathers who couldn’t accept the fact that their son would not follow in their profession. I worked as part of a team, which was particularly important as the number of multiply-handicapped deaf children increased. My greatest emphasis has always been that each child is an individual and that communication is of vital importance. If the child is able to make use of residual hearing, he or she should do so. An education focussing entirely on oralism failed a number of children, although some of those children were able to compensate with better lip-reading skills than those being educated with the help of signing, unless a truly total communication method is used which is unfortunately not always the case. I worked closely with consultants, attending clinics wherever possible. I learned a great deal about middle-ear problems and unusual syndromes, topics barely touched on in my training.

I had the privilege to be involved in the initial plans for the purpose-built School for the Deaf, Heathlands School, and in discussions over which form of communication should be used. It was decided that the approach should be oral with the back-up use of Cued Speech. This worked very well for a number of children but was not meeting the needs of all. After a few years the school switched to using the back up of signs – in theory a Total Communication approach, but the best use of residual hearing was not always apparent.

One of the most enjoyable and worthwhile activities which two colleagues and I ran for several years was the monthly meeting of our mother and baby group for pre-school children when we could observe the relationship between mother and child, help sort out problems, and arrange informal talks over particular aspects.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s the trend away from specialisation in Special Education leading to a more generic approach led to my post being made redundant. For the long autumn term I was Acting Deputy Head at Heathlands School. It concerned me that a number of children were apparently not making the most of their residual hearing. I thoroughly enjoyed my time there, meeting again some of the children I had known as babies. My professional life had swung full circle, beginning in a boarding school for the deaf and ending in a school for the deaf, which had some weekly boarders. For a while after that I assessed children with special educational needs not necessarily with hearing losses, since one of the team was terminally ill.

I kept up my membership of BATOD and then, just as I was thinking I might let it lapse, my youngest grandchild was born in Hanover, Germany, in one of the few hospitals where new-born screening is carried out. This was not universal as it is in this country. At a few weeks old an EcoG confirmed a profound hearing loss. I was there with my daughter and the little one when it was carried out. He was fitted with enormous post-aural hearing aids and some of the worst ear moulds I have ever seen, so feedback was a constant problem. My daughter was told that the deafness was due to the Connex syndrome. She was advised the little one should have a cochlear implant. My younger daughter had always been the best at communicating with my sister. She was very musical and was well aware of the implications of deafness. She and her husband decided he should have the operation. My sister, as many deaf adults, was horrified at the idea of the little one having such invasive surgery. The first time she had seen her great nephew she took him in her arms and said, ‘He’s deaf like me’.

At just under 8 months he was fitted with his first cochlear implant and at the age of 9 months he was switched on. My daughter had worked hard to keep him babbling and I had been a distant adviser. She also took part in a correspondence course with the Elizabeth Foundation in Portsmouth. She was very keen that he should be oral. She had a visiting teacher about once a month. My daughter was advised that, at least to start with, he should be spoken to in German only. At the age of 4 he had a second implant. He remembers the trauma of the operation vividly.

He started school at 4 ½ and had the same teacher for the four years of the Primary School, who did her best to integrate him into the class. The health insurance company refused to provide him with a radio aid but a friend of my daughter’s had a contact and the company donated an aid to him. He was recommended for a grammar school placement and he now attends a grammar school in Hanover and is in the 8th class. In the 3rd year of the Primary School when he started to learn English at school my daughter began to speak English to him at home. He is now almost bi-lingual though his written German is probably better than his written English. He also learns French. He finds it very difficult, virtually impossible, to follow recordings in any language. About once a year he gets a visit from a Teacher of the Deaf. He has a radio aid, which the school has provided for him, but it is not always used or checked that it is working properly.

He does remarkably well but it is difficult in a class of thirty and it is not appreciated under how much strain he is. He does not like to admit if he has not followed. He has found it difficult to make friends and is going through the difficult teenage years at present, trying to come to terms with his deafness and having an English mother. People who speak to him on a one to one basis feel there is no problem; he has a clear musical voice but in a group you can see how he seeks the faces of each speaker in turn. He is in the deaf and the hearing world but not quite secure in either. When I think of my happy well-adjusted sister I sometimes wonder, yet Rupert can use the telephone, travels independently long distances by train and is achieving academically far more than she ever could.

I planned to retire on August 31st because by then I shall have completed, to the very day, forty years as a teacher for Surrey County Council. It seems incredible that I have been on the job for so long, until, that is, I look back and realise just how much everything has changed since I first started teaching.

I’m not sure how I came to be a teacher. I really wanted to be a housemother for children in care but, as I couldn’t cook, I thought that they wouldn’t have me. My friends in the 6th Form were mostly going in for teaching and that’s really why I applied.

I went to Teacher Training College in Brighton. In those days the course was two years. Both the college and my study bedroom were situated on the sea front. College rules were strict. It was really an extension of school. Men were not allowed in students’ rooms, except for tea at weekends if another student were present. Staff, for some reason, called the students by their surname alone, as in boys’ public schools, and this habit was picked up by the students and used among themselves. It was post-war, and several foodstuffs were still rationed. I remember that I managed on ten shillings pocket money a week. That would be 50 pence. For school practice, we had to make all our own teaching equipment: exercise books, flashcards, reading and number cards and games, wall charts, teaching pictures, handwork models and even individual bean bags for throwing in PE. I think I still have mine somewhere.

I began teaching in 1952 at the age of twenty. My starting salary, gross annual, was £370, which I thought an enormous sum. Male teachers received more. My first post was at Fortescue Road School in Colliers Wood, which was then in Surrey and was a Junior School in a disadvantaged area. I had a lower Junior class and for the first four months I was convinced that I was in the wrong job. I had no idea how to achieve class discipline and was very unhappy until one day the deputy head took me aside and suggested that it was no use trying to teach anything until I had a quiet class, but didn’t explain how this was done. The next day I was feeling unwell and the class as usual was being noisy. Suddenly I could stand it no longer and shouted “Be quiet!” There was dead silence. I don’t know who was the more astonished – the children or I. But from that moment I began to gain confidence and to learn class control, without shouting. Eventually I was happily taking sixty girls for weekly games lessons in the hall.

All schools in those days had a distinctive smell which hit you as you walked over the threshold. It wasn’t the lavatories because they were across the playground. It was a combination of carbolic disinfectant and school ink which had to be mixed from a powder. When I first went to the school I rearranged my children’s heavy iron and wooden double desks into groups instead of straight rows. The school caretaker took one look and marched to the Head to complain that he would not be able to sweep the classroom floor properly, so back they had to go. I was ahead of my time. I asked if I could have exercise books for topic work, but was told that if I wanted extra, I would have to make them myself. There were no guillotines or staplers. I had to cut up large sheets of drawing paper with scissors and sew them together by hand.

At lunchtimes staff on dinner duty had to march the children in a crocodile to the school canteen half a mile away and supervise their eating. For this we had the reward of two free dinners a week. All school dinners were meat and two veg., and most teachers took advantage of a subsidised hot meal.

Friday afternoons saw a dreaded ritual when class teachers had to add up their registers. The horizontal total of attendances had to equal the vertical daily total. Then we had to do a long division sum to find the percentage attendance. There were no calculators and maths was never my strong point. The school secretary couldn’t go home until the total figures had been sent in, so children had to be occupied until every error had been located and corrected. On Monday mornings there was dinner money and national savings to collect. The total on paper had to agree with what was in the tin. Of course, it was pounds, shillings, pence, halfpennies and farthings then. At that school, even the staff called each other Mr, Mrs or Miss So-and-so.

I stayed at that school for three years and then my family moved from Wimbledon to East Horsley. I obtained a post at Merrow Church of England Primary School outside Guildford. For interviews a hat and gloves were still worn. This school had been built in 1853 and the building had been condemned in 1939, but it was still functioning. There were four classes for children aged 5-11 years, so each teacher had a two-year age-range. I had forty children aged 7-9. I took over from a retiring pupil teacher who had never had any training, but who had stayed on at the school where she had herself been a pupil, for fifty-five years. So that was a little piece of history. That was a real country school then, and I was very happy there. Cows in the adjoining field used to rest their heads on the playground wall and watch the children. I used to say that if I grew tired of looking at children’s faces, I could always gaze through the classroom windows at the cows.

We staff used to eat our school dinners in the orchard on hot summer days. I used to cycle a hundred miles a week to and from school and evening activities. Heating in my classroom was provided by an enormous black stove which the female caretaker had to light every morning and which was very temperamental when the wind was in the wrong direction. One morning a raw young curate, who had come in to take Scripture, stood himself right in front of the stove. No sooner had he started talking to the children than a huge cloud of grey smoke billowed forth from under his cassock. I shall never forget the desperate appeal in his face as he looked towards me to rescue him from a supposed early martyrdom. Now there is a new school next door, and where cows once grazed a huge housing estate has sprung up.

I stayed at that school for six years and that was where I really learned to teach. I wasn’t keen on applying for a deputy headship but decided to branch out and teach disabled children. I tossed up between the blind and the deaf, and chose the latter. I applied to Portley House School, Caterham, Surrey’s only residential school for Junior Deaf Children, and did a year there before going on to Manchester to qualify. I went to Portley House, never having even seen a deaf child in my life. My first class consisted of four ten-year-old children, specially chosen for me because they had the best speech in the school. But for the first month I couldn’t understand a word that they said and they seemed not to comprehend anything that I uttered. “You’ll be all right,” said another teacher. “You have a big mouth.” She meant, for lip speaking. Leo Murphy was deputy head and Elizabeth Hillman had already been there a year when I arrived. The only subjects taught were language and arithmetic in the mornings and handwork and games in the afternoons. Hearing aids were still a fairly new idea. Surrey favoured the Multitone aid and each child’s was worn clipped on to his or her vest, underneath their clothes, and for school lessons only. I now believe that the aids were switched off most of the time. Many children only went home at half-term and end-of-term. Resident staff did a compulsory fifteen hours overtime a week. This eventually comprised one weekend in four and a weekly sleep-in duty. I once slept in the attic duty-bedroom the night before its chimney stack was struck by lightning.

When I went to Manchester in 1962, I had an advantage over most of the other students, in having had a year’s experience with deaf children, and was able to make more sense of some of the lectures than those who hadn’t. Professor Ewing was at the helm in those days and his lectures were particularly difficult to follow, because he always began with point one, and after waffling on for a bit, continued with point 6. My term’s school practice was at Odsal House in Bradford, under a horrid headmistress, whose aim in life seemed to be to have her pupils, and certainly her students, in tears. I escaped this indignity, being already an experienced teacher and knowing what I was supposed to be doing and why. My male class teacher’s method of keeping discipline was to throw chalk with swift, unerring aim at inattentive pupils. One of those children stole £5 from my handbag, which probably explains why I have never since carried a handbag to work. In the nursery class I particularly recall a deaf-blind seven-year-old who used to sit on the floor behind the classroom door all day. She put herself there because it was the only place in the room where nobody could fall over her. She was never given anything to do.

Shortly after returning to Portley House I was promoted to the first graded post in the school, with special responsibility for all the hearing equipment. This is amusing because now I am the least technically expert member of the peripatetic team. Anyway, the first thing that I did was to design and have made a harness for each child to wear his/her aids on top of their clothes. Teachers could then see whether or not the aids were switched on. I made sure that boarders wore theirs in the evenings and at weekends despite their strong protests. I fought battles royal to get better-fitting ear moulds, and this is going back thirty years. In those days, they were made by a deaf dentistry technician, who had never worn hearing aids and who didn’t appreciate feedback problems. I also insisted that each child wore two aids, although for some time the second had to be an OL 56, absolutely useless for the severely deaf, until Surrey became more enlightened, and purchased two commercial aids for in-county children. When Philips Co. began a same-day-repair service, I recommended a change-over to Philips’ aids and we then had a choice of model to suit different hearing losses. My class benefited by having the school’s first Connevans Group Hearing Aid and later, a radio mike.

I stayed at Portley House for thirteen and a half years, teaching gradually younger and younger children. When Donnington Lodge School for Infant Deaf Children in Berkshire closed, we took nursery and infant children as well as juniors. We even had one two-year-old boarder. At different times while I was there, Suzan Downing and Ruth Russell came into my class as students from the London Course. Later Margaret Dickens joined the staff and Sue Richardson did some supply teaching with us.

I had never much fancied the idea of branching out into the peripatetic service, as I had considered the work too piecemeal, but eventually I felt the need of a change before getting into a rut, and so joined the service seventeen and a half years ago. Diana Brook, who had once been a peri in Guildford, took over my classroom at Portley House, and I moved to Guildford.

The heavy converted audiology vans had just been withdrawn by the County and peris were expected to use their own cars. The changeover of job came as quite a shock. At Portley House I had imagined that I knew most of what there was to know about deaf children. The world of hearing-impaired children in mainstream school was a completely new challenge. In those days we had the whole age-range from birth for children at-risk, until they left university in some cases. In Leo’s day, there was a deaf University student who couldn’t cope, and who hid himself in his room for six months, while still drawing his grant, before anybody knew he was there. My greatest difficulty at the beginning, was how to deal with babies, as I had never had anything to do with babyhood since leaving my own. Dr Beet took all the clinics and he was a real gentleman, always rising from his seat when I, or any of the mothers, arrived and departed. I had to learn by trial and error how to teach hearing-impaired babies and toddlers. At one stage I had twelve pre-schoolers. In those far-off days we were not just teachers to pre-schoolers and their families, but unofficial speech therapists, social workers, housing officers, careers advisors, marriage guidance counsellors – and I even found myself being asked for advice on family planning! As to appellations, County Hall has on two occasions called me a peripatetic teacher, unattached. My bank manager, who doubtless himself needed a hearing aid, once wrote down my occupation as “Teacher of Death”. Like the rest of you, I have been called “The Deaf Lady”, “The Audiometrician”, “The Nurse”, “The Doctor”, “The Toy Lady” and, the one I like best, “The Special Lady”.

The job has its hazards:

- Have you ever been in a house where your pre-schooler’s mother has shut his younger brother in the room with the two of you because she couldn’t stick him any longer?

- Have you been in a house where a child’s dirty nappy was removed by mother and left on the table, while the child wandered round bare-bottomed looking for a lap to sit on?

- Have you had a child present its full potty to you instead of to mother, as a sign of your acceptance as one of the family?

- Have you had a pre-schooler’s neighbour, in a dressing gown, call you across the road and ask your advice, because it was thought that two tablets had been taken instead of one and what should be done about it?

- Have you been in a school’s medical room doing a hearing test, when a teenager has burst into the room and promptly been sick into a bowl on the table beside you?

- Has your car had a puncture outside a school, when the father of the child you were visiting, offered to change the wheel for you, and systematically proceeded to destroy your jack and a teacher’s borrowed jack and the metal embellishing strip on your car?

I have been asked what I am going to do in retirement. Well, first I want to move to Sussex which I have loved ever since college. Then I want to do some writing. I wrote one book, years ago, had it privately published and sold a thousand copies. Also, in the days when I had time and energy to spare after work, among other things I wrote and directed two son-et-lumières and a village pageant for fifty actors and choreographed and directed several children’s musicals. I plan to do lots of different things and have a complete change.

“an awful lot of people are giving a lot of time to this – I wonder whether anything will become of it?”

A Teacher of the Deaf in her diary in 1987…….. and the beginning of cochlear implants for children in the UK … me!

So, how did I get there and what happened? … After qualifying as a teacher I taught young hearing children for six years in the north of England and had the opportunity to observe child development at first hand. I also experienced unexpected satisfaction when the children I taught developed a passion for reading, and an enjoyment of books. Many of these children came from homes where reading was not a common activity and where books were unavailable. The importance of the acquisition of literacy skills in these children became apparent; however, I was teaching literacy skills to children who had already acquired the language of their home and one took for granted that they came to reading with appropriate linguistic skills. A friend’s deaf baby made me think again – I had only experienced deafness in old people, and hence thought of it as a communication challenge for the elderly. My naive assessment was that there was little more to deafness than that. I had overlooked the fact that children are not born with facility in their home language and that this develops, over years, through parent/child interaction, and that hearing usually has a significant role to play in this. The frustrations of both child and parents were immense and the hearing aids of the time gave little auditory information. They chose to learn sign language, which supported her communication development but did not provide the ease of communication they had with their other child, who was hearing, or access to spoken English. For the first time I realised that the challenge of childhood deafness was not one of communication, but of spoken language development.

Relocating to Birmingham in 1976 I had the opportunity to train as a Teacher of the Deaf, and once more I was fortunate to have inspiring tutors and Teachers of the Deaf to work with. At this time there was a growing interest in the psychology of deafness and the impact of deafness on the social and emotional wellbeing of the child and family; this opened up areas of study previously unknown to me, as did reading the work of Chomsky and Crystal on “normal” language development. There were also huge strides being made in audiology services, with the first post-aural aids being introduced, the first family services and peripatetic teaching services for deaf children supporting families in the use of what were then the latest hearing technologies. The new work of Ling and Pollack in the 1970’s in utilising hearing through auditory training tapped into my previous knowledge of physics and maths, and enabled me to understand most of it.

There was also a growing awareness of the Deaf community as a minority group with its own language and culture. Visits to a range of schools for the deaf made one immediately aware of the passion which surrounded the controversies about how deaf children should be taught, whether orally or by sign language. Meeting deaf adults in schools for the deaf, and meeting those who espoused oral methods further complicated my thinking. If children couldn’t hear spoken language, how were they to develop it and how could oral methods work? Yet those learning sign language, with its own grammar, found it difficult to access the curriculum in English – or to communicate with parents and siblings or the hearing world. The conviction of the various proponents amazed me, coming from the more straightforward world of mainstream education, and were difficult to comprehend. Often the teaching methods used with deaf children seemed at odds with what I knew of child development – and yet one felt instinctively that they were children first with the needs of a child – and deaf secondly.

After qualifying as a Teacher of the Deaf, I worked in a residential school for the deaf which supported very challenging children from throughout the UK using sign language. Teaching deaf teenagers with very delayed communication skills and language levels taught me at first hand the impact that deafness can have on social and emotional development as well as on linguistic and educational attainments. Moving to an oral day school for the deaf gave me opportunity to observe other methods at work and to observe the impact of deafness on early language development. I also came to realise the complex profession I had joined. These teachers were passionate about the children they taught and their needs and the controversies I had read about came to life daily in the staff room discussions. Deaf education was indeed facing major challenges but there was little consensus about how to deal with them.

Relocating again, in 1980, gave me the opportunity to manage a resource base, or unit, for young children in a mainstream school. This brought fresh challenges – to manage deaf children with their hearing peers, within a non-specialist setting, and to work more closely with their families. Throughout these years of teaching deaf children one was constantly made aware that what had been taken for granted with hearing children was not possible with these deaf children, and teaching them within a mainstream environment made this apparent every day. Each new word or concept was taught by someone – either by their parents or myself, not learnt through overhearing them in the usual way. Acquisition of language was not a natural process – it was a teaching process. Parents and I shared home/school books in an attempt to share our knowledge of these children and to facilitate communication; without this it was impossible to understand what the children were trying to tell us. New vocabulary at home and school was shared – we could both make accurate lists of the words these children knew because we had taught them – the children had not acquired them by hearing them. I became adept at simplifying language to make it understandable. Yet I was determined that we should not concentrate on the “mechanics” of speech and language learning – the joy of communication and learning seemed essential and was not often present in some of the rote methods I had observed.

However, hard as one tried, enjoyment of reading seemed to be missing as reading sessions became reduced to language teaching sessions. Sharing a book with a young profoundly deaf child in the days before implantation and today’s technology, was impossible as the child could not look at the book and understand what the adult said at the same time, without visual clues. These children did not come to reading with a knowledge of the language or of its phonology – these had to be taught. Reading skills used by deaf children and their teachers were different from those I had used with hearing children, and clearly were not helping the children to read effectively – or with enjoyment.

The negative impact of deafness and linguistic delay on emotional development was often increased by the behaviour of carers, and the effect of over-protection. One observed children’s behaviour being excused because they didn’t have the language or vocabulary to understand the issue – how did they become mature adults if they weren’t expected to take some responsibility from an early age? How did one generalise language learning, and facilitate progress through the cognitive stages I had observed occurring in hearing children? While all this personal thinking and close observation were going on, the children I taught were frequently the subject of researchers, who would observe them in school. Their research reports rarely threw any light on the issues I thought were important, and rarely took account of the many factors which influenced the behaviour they were observing. Their interpretations were often simplistic – I became increasingly aware how many factors influence the development of deaf children – and how heterogeneous they were as a group. Levels of hearing loss, use of hearing aids, aetiology or parental input rarely appeared as significant factors in research reports.

During the 1980s the Deafness Research Group was established at Nottingham University, led by David Wood, and gave an opportunity for an objective assessment of the challenges in the classroom for deaf children, with practitioners being taken seriously and with rigorous academic input. The work of Wood with Margaret Tait, studying early communication with deaf children, looking at reading and storytelling techniques, caused me to think about a research degree. The option to carry out an action research degree allowed me to learn more about qualitative research techniques which seemed more appropriate to the observation of these children, and which threw light on the influences on their development, rather than hiding them.

While carrying out my research degree in 1986, I began teaching a boy who had lost his hearing following a fall, and his audiologist, Barry McCormick, began to think, with his mother, about a cochlear implant for him. The boy received only vibro-tactile sensations from the most powerful hearing aids available at that time; his speech deteriorated and accessing the curriculum in a mainstream class became almost impossible. The trauma of losing his hearing entirely at the age of six was devastating for him and his family. At that time, the only option was the RNID single channel cochlear implant, available in London, but only if he were an adult. If I had thought that deaf education gave rise to controversy, the consideration of a cochlear implant for a child was to arouse even greater passions. Investigations and meetings took place, with little family or local involvement, and operation dates came and went as the child and family became increasingly frustrated. After two long years of fighting and living on an emotional roller coaster, he had his single channel implant in 1987 at University Hospital, London, and we wrote it up as a multi-professional case study (Archbold et al, 1990).

Another mother soon became important in the story – in 1988 a boy lost his hearing through meningitis, and his mother determined to obtain a cochlear implant for him – prepared to travel to the US if necessary. The need for deaf young children in the UK to have the opportunity offered elsewhere was urgent – while the arguments persisted, these children were missing out, and the skills needed were available in Nottingham at the Children’s Hearing Assessment Centre, Queen’s Medical Centre, the Medical Research Council Institute of Hearing Research. A charity, The Ear Foundation, was established to fund the first operations, and established the team to carry out the first multi-channel implants in the UK. As a Teacher of the Deaf, I was appointed as Co-ordinator, to establish protocols, and coordinate the business management which was later to lead to the Nottingham Cochlear Implant Programme, when the National Health Service took on the service.

The opposition to this development is unimaginable today – it came not only from the Deaf community, viewing paediatric implantation as a threat to their culture, but also from the voluntary sector, audiology services, educational services, medical services and from some in the cochlear implant community. Some felt children should not be implanted at all, others that they should wait until old enough to make their own decisions, and others felt that any implant team should implant adults first, and only then move to implanting children when experienced with adults. Very difficult meetings were held at which parents received very personal criticisms, and professionals on the team were threatened with professional ostracism and received personal hostility. At a personal level, it was professionally a challenging time: the majority of my colleagues did not support what I was doing and I felt professionally threatened. In addition, leaving the world of education and entering the medical world, where implantation was inevitably carried out, with its differing authority structures and differing priorities, was a huge challenge and one at which I felt not a little personal and professional disquiet.

However, the range of like-minded professionals necessary to implant children was in place, and families were determined to proceed. I then coordinated the multi-professional team and the work necessary to gather the evidence to support cochlear implantation in children. Working with scientific and medical researchers led to an awareness of the importance of rigorous monitoring and the opportunity of ensuring that measures of outcome important to parents, children and teachers were considered, not only changes in hearing abilities. As Co-ordinator, and with my professional and personal background, it was a huge opportunity to ensure that these areas were included from the outset in both practice and the evaluations which were to be carried out. Thus the data and the papers which resulted from the collection charted the period of greatest challenge and opportunity for deaf education – the introduction of cochlear implantation – and for me, a fascinating period as a Teacher of the Deaf.

So, as I come to ‘retirement’ what are my observations? Children with cochlear implants are the most researched group of children there have been: outcomes from cochlear implantation have been collected over long time-frames and in a variety of domains and the evidence is clear. Children implanted early in the first years of life, and without complex additional difficulties, can almost always acquire language through hearing and their opportunities are transformed. They hear well enough to acquire regional accents and overhear the language around them, use the telephone and enjoy music and other languages. Their outcomes are measured now on assessments standardised on hearing children: their literacy levels, so important to me, are increasingly within the normal range. The language of the home, which in 95% of cases is a spoken one, is available to them.

However, they remain deaf, reliant on technology for access to spoken language, and in noisy, reverberant situations mishear, misunderstand and the challenges the long-term management of this technology at both home and school are too often not addressed. There has been a huge focus on a medical model of follow up care rather than an education and social one; whether this has been necessary is debatable. Too often the management has been the responsibility of those who focus on listening skills and not on the child’s development, including the role of audition.

This has all taken place at a time when there have been huge societal changes and expectations, great communication technological developments as well as other hearing technologies and financial austerity with influences on how services are delivered. For deaf children, the introduction of newborn hearing screening has had a huge impact on their lives. In addition, improved medical care has led to increasing numbers of premature babies surviving with complex needs, of which deafness may be one.

So ….. I have been privileged to be part of this dramatic change in opportunities for deaf children, in the UK and internationally. I see profoundly deaf children achieving things I wouldn’t have previously have envisaged possible, and viewing their deafness differently. Listening to them, they tell me that being deaf is different today, that they can be both hearing and deaf … and they view themselves flexibly, as of course do most young people today. So, the role of the Teacher of the Deaf is both the same and different from what it ever was …. but it is under threat from many sides. It is both the best time, and the worst time, and I am not sure that we are making the most of the great opportunities that there are for deaf children and young people today, while I still hear some of the same old arguments. Let’s listen to the young people themselves as they have many platforms to tell us!

Family Links with deaf education

My contact with deaf education began at birth. Born hearing but into a deaf household, my first three years were spent during the Second World War with maternal grandmother, deafened by a virus aged six, grandfather born profoundly deaf and educated at RSD Margate – both were from hearing families who lived in Gravesend, Kent. The families encouraged the pair to marry because they were deaf.

I learnt from an early age to communicate differently with them: mouthing sentences to grandmother who used spoken English but without voice, and much fingerspelling and gesturing to grandfather, using some isolated signs and a little fingerspelling.

Aged three, I moved with my parents – father was demobbed from the RAF, to a prefab in Northfleet, but close contact with deaf grandparents continued. In 1950 we all – parents, grandparents, my younger sister Lesley and I – tumbled into my father’s large old car and travelled from Gravesend to Margate to visit Margate ‘ASYLUM’ for the deaf.

The old Margate deaf and dumb asylum

I remember being shocked, for my concept of ‘asylum’ was a place for the mentally ill, but mother explained it meant ‘a place where you are looked after’. Grandad looked round the old building where he had been taught, but there were no children there. They were playing in a new area to the right of the old school. ‘Go and play with them’ mother told Lesley and me. We hesitated but the deaf children were welcoming, showed us their rabbits and, interestingly, pointed to one boy to show his different coloured eyes, brown and blue – an early introduction to someone with Waardenburg syndrome. I suddenly realised that, although we could mix comfortably with the children, our communication was not good enough for in depth conversation. Why?

My sister and I had been advised by grandmother not to use sign language. She had been told at her boarding school in London that it was only for animals. Thus our communication with grandfather and anyone who used sign language was very limited. This advice given to her by Teachers of the Deaf had disastrous consequences for our family.

At about the same time as the visit to Margate, my sister and I went to a deaf club party in Chatham, Kent. I remember vividly our first deaf game of musical chairs when we had to fix our eyes on a waving handkerchief and grab a chair to sit on when the white ‘flag’ stopped. I was fortunate to be exposed to deaf culture and behaviour during early childhood, learning how to attract attention, interrupt signed conversations and join in humour. My mother told me that the ‘slapstick’ scenes in the silent movies, enjoyed very much by her parents, were being replaced by the ‘talkies’ with no subtitles causing an end to the family trips to the cinema.

The disastrous consequences of the no-signing policy affected my grandfather most. At Margate he completed his education in 1907 and had been trained to be a basket maker. Vocational training in schools for the deaf is a strength that gave deaf school leavers skills to enable them to make a living. Grandfather was helped by local missioners to obtain employment. However, he spent long hours, isolated, alone in workshops puffing on his hand rolled cigarettes. I often wondered what he thought about every day at work. My mother once took my sister and me to see him at work; he sat on the floor in damp conditions necessary to keep the cane supple.

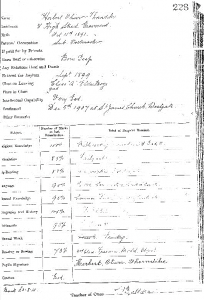

Grandfather, Herbert Thorndike, at work

I concluded that two major factors contributing to the isolation of deaf people at this time were:

- Segregation in residential schools away from the general population

- The inability of the hearing community to sign owing to lack of exposure to deaf people who signed.

Thanks to a colleague and fellow student at Manchester, Julie Gemmill, who became vice principal of RSD Margate, I obtained a copy of my grandfather’s leaving report. I am also grateful to Peter Brown, archivist at Margate, for showing me the actual copy. of the report in the Margate archives. The report makes interesting reading, giving a picture of the curriculum at the beginning of the 20th century including subject such as ‘History of the British Empire, Manual Work, Speech, Articulation, Lipreading’.

I was amazed to see that Herbert gained 85% for articulation and 88% for lipreading. Strange as in adult life he never used speech, just made ‘mmm’ sounds and low frequency vocalisation. When I hear similar sounds used by Deaf male friends and colleagues I associate them with my happy childhood with deaf grandparents.

Training to teach hearing children

Since the age of four, when I started infant school, I decided I wanted to teach. The motivation was to show my infant teachers how to meet my learning needs better. On the first day, having been put on a mat with the rest of the class to sleep after lunch, I woke, frightened to find everyone had disappeared. Not knowing the layout of the building, I had to find the class by locating the noise from the hall where they were singing and dancing in a ring to nursery rhymes. I also felt time was wasted copying sentences of print and it took me a while to work out that the shape for ‘a’ meant ‘a’. I felt there was not enough explanation generally, possibly because of my being from a mixed deaf/hearing home, interpreting and explaining carefully were daily activities. I enjoyed explaining and explaining information clearly, skills which I consider every teacher must acquire and develop.

I loved school and was sad to see some others did not enjoy lessons. From 1961 for three years I trained as a middle school teacher at St Katharine’s Church of England teacher training college in Liverpool. My southern accent, although with slight estuary vowel sounds, was considered ‘posh’ by fellow students from Yorkshire and Lancashire. On teaching practices, I was aware that I did not relate to the pupils in schools in Liverpool and Birkenhead who had strong Liverpool accents in the same way as I did with children in Kent. This was a useful awareness experience that later I could relate to the differences in regional signing when mixing with deaf teachers and professionals, though the realisation took much longer.

My first teaching posts were in Hampshire where accents were similar. This was the most fulfilling period of my teaching career, relating to hearing children, identifying with them easily and enjoying learning from them as well as teaching them.

By coincidence there was a ‘hearing-impaired unit’ attached to one of the schools and for one year the governors and head could not recruit a Teacher of the Deaf. Also for one year there was only one severely deaf pupil in the unit. The head was aware I had deaf grandparents and asked if I would include the pupil, HP, in my 4th year B stream junior class. Of course I was delighted, but it certainly provided a great learning curve for me and the rest of the class.

Poor HP struggled to follow mainly by lipreading us all but became a star during drama lessons. He organised his own sketches that were mostly mimed, and we, the hearing class and teacher, were astounded. We adapted to HP but he had a tough year and hopefully was more relaxed when he went off to Mary Hare for his secondary education.

Training to teach deaf children

Hampshire kindly seconded me to train as a Teacher of the Deaf at the audiology department in Manchester in 1968. I had a shock! Firstly, we were told that deaf children had no language, that signing was not a language and that all deaf children would learn to speak English if they had the appropriate amount of amplification using correctly prescribed Medresco hearing aids with individual speech training sessions with speech trainer and mirror.

I remember having my first essay on the impact that deafness had on children returned to me with the comment that I had left out a section on how deafness prevents deaf children from developing language. Later I realised that it was because I did not think signing prevented language development having been exposed to sign language and seeing effective communication at home where it was used.

Another memorable failure I encountered was transcribing a paragraph of English into phonetics. Rings appeared round symbols for some vowels to show errors. Mystified, I saw my tutor and we both realised that her northern pronunciation was different from my southern. Fortunately, she accepted my interpretation. It is surprising that this difference in local accents had not arisen before in this exercise.

Staff at Manchester were strong on research, but not very experienced in teacher training. I became a staunch advocate for the abolition of end-on teaching to qualify students straight from degree courses and a rule that teachers with at least three years teaching should be recruited to train to teach deaf children so that they would have an idea of the attainment levels expected in mainstream education. Without that experience there is a danger that expectations of deaf children are too low.

Educating deaf children

After completing the Manchester course, I chose not to return to Hampshire, where a teacher of deaf children had been recruited for the unit and a vacancy occurred in the small residential school in Basingstoke. Instead I was appointed as a peripatetic Teacher of the Deaf in Huntingdon and Peterborough where, as in many other authorities during the early 1970s, there was a move to open units, placing fewer children in residential schools far from home.

During this period, I concluded that many peripatetic Teachers of the Deaf spend little time actually teaching. There is a need for careful management of time, minimising travel time and ensuring pupils do not miss important lessons when withdrawn for one to one sessions by consulting them over timetabling. The Head of Service, Cedric Jones, wisely timetabled me to teach in units giving unit teachers the opportunity of carrying out peripatetic work. I enjoyed teaching groups in units and to see the delight of pupils when post-aural aids became available on the NHS. There was a thriving branch of the NDCS in Peterborough, which offered valuable experience working alongside parents.

Peripatetic work; learning from deaf parents

My timetable included attending clinics where the diagnosis of deafness took place and follow up home visits to babies and preschool toddlers. Sessions included the checking and assessment of the use of aids and auditory equipment, language encouragement and chats with parents.

The most enjoyable visits were to families where parents were deaf. This was because there were no or very few problems of emotional adjustment or communication. In fact, several deaf mothers taught me the importance of showing the little ones how to use their tactile sense fully, for example giving them extra time to feel containers, lift and shake them. Whilst chatting, to my bewilderment a deaf mother regularly leant back on her chair to feel the French window. On enquiring why, she told me she was checking if her husband had returned from work as the vibrations from the car could be felt through the glass. What useful tactile techniques would be passed to her deaf children! Experiences with deaf parents convinced me that they should be involved in assisting hearing parents enriching the lives of their deaf offspring.

Fortunately, in my last full-time job, Head of the Hearing-Impaired Service for Bedfordshire and Luton, I was in a position to advise the authority to recruit deaf parents and adults to teach deaf children and help parents to communicate effectively with their deaf children. When the service ceased in 1993, owing to local government reorganisation, there were seven full time deaf employees: one fully qualified Teacher of the Deaf , 4 teachers of BSL and 2 teaching assistants. There were also deaf volunteers who helped run the summer youth club.

On one memorable occasion, I went to collect a primary aged child for youth club, whose mother did not speak English. To my surprise she signed to me asking where he was going and what time would he be returned. We exchanged information easily in BSL although we could not understand each other’s spoken language. Thanks to the peripatetic visits she had received from one of our BSL tutors, the language barrier was broken.

After early retirement I continue to be indirectly involved in supporting deaf people, some ex-pupils, in different ways and they help me enjoy the communication and culture that is part of my heritage.

I shall probably never know what it is like to be deaf and really understand how my grandparents and deaf people of all ages with whom I have been in contact, manage their lives. However, it has been a privilege to have been allowed to participate in the education of deaf children for the most part of my career. I hope one day, deaf people will be welcomed and appreciated in deaf education and be appointed to higher positions of responsibility to which they are entitled.